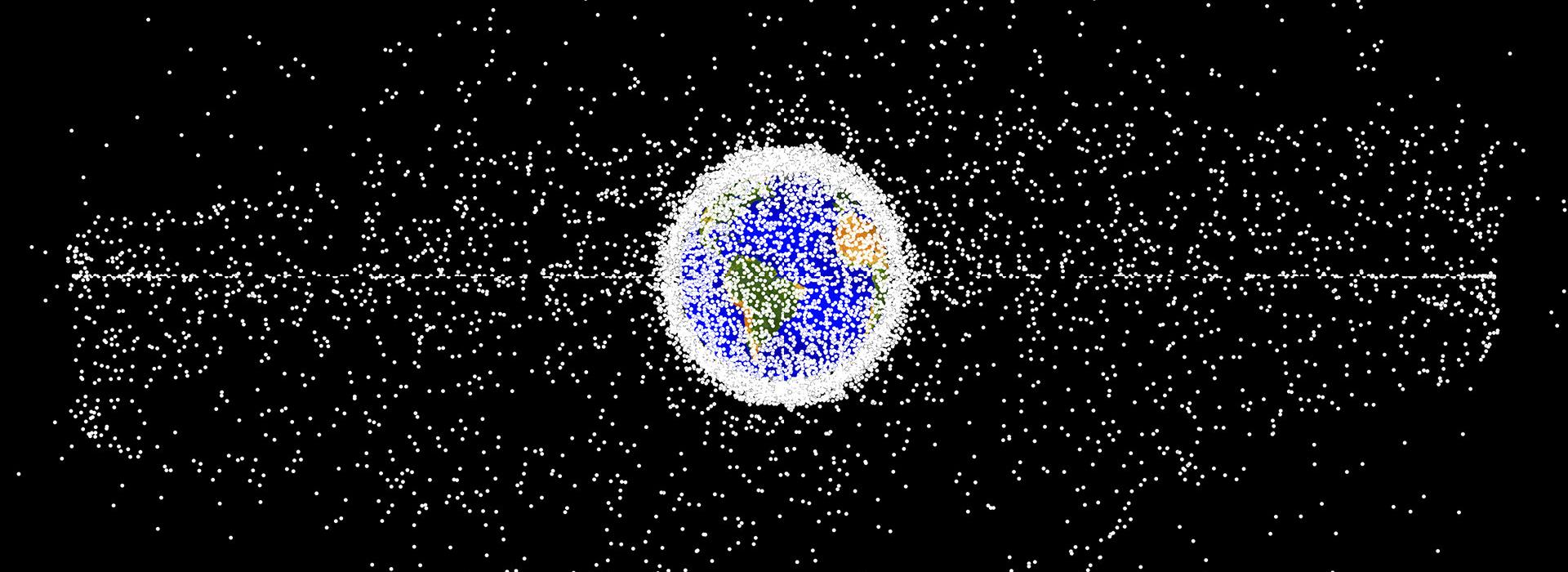

NASA 2019 computer-generated image of space debris being tracked in Earth orbit

In Oregon State’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, faculty members and students conduct research that is used to solve a lot of complex problems, including those presented by climate change, earthquakes, environmental contamination and shifts in ocean ecology.

The loads of space junk circling the Earth might seem to be outside of the college’s purview – “Earth” is part of the name of the place, after all. But the connection was made by graduate student Keiko Nomura, who worked on the project with an interdisciplinary team she met at a month-long workshop at the Santa Fe Institute, an institution renowned for the study of complex systems science.

Originally from Long Beach, California, Nomura knew she wanted to go into a field that would help her protect the marine environment she grew up loving. As an undergraduate at San Diego State University, she studied environmental sciences and biology, and conducted research in intertidal ecology.

“Watching and questioning the intense coastal development in California as I was growing up, I wanted to move towards something policy- and management-relevant,” she says, which is how she found the Marine Resource Management master’s program within CEOAS.

For her MRM project, Nomura worked with geographer James Watson on a project related to small-scale fisheries on the Baja Peninsula, Mexico. She used a data-centered approach to examine the capacity for these fishers to adapt to environmental (and other) change, given the range of fisheries they participate in. She enjoyed that project so much that after earning her M.S. in 2020 she decided to expand on it, staying on with Watson for a Ph.D. as well.

About two years ago, she learned about the Santa Fe Institute and was intrigued. The complex social-ecological systems she studies are often analyzed using network analysis, a central focus of the institute. A course there allowed her to hone her knowledge of complex systems analysis and meet others doing the same.

The program involved classes and guest lecturers describing work using systems analysis on everything from archeological settlements to physics to family dynamics. Students were also required to form small, interdisciplinary teams to use the tools of systems analysis to examine a problem of their own choosing. Nomura’s team included physicists, a linguist, a neuroscientist, an archaeologist and a journalist, among others. At her suggestion, the team chose to examine the sticky problem of the proliferation of space debris.

“Part of the point was just to try ridiculous stuff – if your project dies, that’s fine, that means you’re being risky,” she says.

The problem of space debris is this: Pieces of junk – defunct satellites, items dropped by the International Space Station – can collide with satellites that we use for everything from communications to navigation to tracking environmental parameters of our planet, damaging or destroying them. They can also, from time to time, fall to Earth, with a range of potential consequences for people and infrastructure.

Of particular concern, and the focus of the team’s modeling, is a scenario called Kessler Syndrome, a tipping point which is predicted to occur when so much debris orbits the Earth that pieces smash into each other, breaking into more pieces. These pieces cause more collisions, and so forth, in a kind of viral reaction. This state could make some orbits around Earth unusable, preventing future satellite launches.

The interdisciplinary team got to work. The physicists and neuroscientist modeled the physical problem. The linguist and the archaeologist started framing questions about use of global common resources, colonization and ecosystem services. Everyone had a role to play on the wildly diverse team.

Using data on existing amounts of debris, the team developed a mathematical model in which they manipulated parameters like launch rates and debris cleanup activities in order to predict the future of space junk encircling the Earth. They concluded that we may already be immersed in a Kessler Syndrome state, although with good management of the problem we can still avoid the positive feedback loop that results in hopeless clogging of orbits. Without additional management, debris congestion is likely to occur within 200 years, the model suggests. The group also explored questions of governance and remediation, and the social and geopolitical forces that influence both. They published their findings in a paper in the International Journal of the Commons.

“One of the things we found is that it would be really useful if we could start removing debris now,” Nomura explains. “There are companies that go up and remove this debris, but there aren't enough market forces pushing in that direction right now,” nor does the mushy governance of space provide much leadership or incentive. Besides removal, other approaches could be used, including planning for the senescence of a satellite when it is launched by including a small amount of fuel and a thruster that can direct the satellite towards Earth to burn up at a designated time.

Nomura sees many intersections between this work far above the Earth and her work with fisheries down here in the ocean. For one thing, space and the high seas (beyond the territorial waters of individual nations) share the problem of being global expanses with unclear governance that contain what should be shared resources.

“The United Nations, which kind of manages Earth’s orbit, calls it ‘the common heritage of mankind,’ and it’s arguably the same for the high seas,” she says. “It belongs to everybody and belongs to nobody. With distant-water fleets and foreign fishing we’re moving into that ocean space more and more. While there are some international agreements in place for some areas, it’s still kind of a Wild West. I see a lot of parallels with space.”

“Another parallel I see is that access to space and access to distant, productive fishing grounds are both limited to wealthy players that are able to develop the right technologies,” she adds. “There’s unequal access and unequal distribution of benefits.”

Given the shared nature of the resource in question and the dire consequences for inaction, this crisis may sound depressingly familiar. Nomura agrees, but her outlook on the issue is actually positive. “I feel strangely optimistic about space in that I hope we've learned some lessons from Earth’s environmental issues,” she says. “I’m hoping we can learn from our experience with climate change how to cooperate a little bit better. I think we can have faith in humanity.”

Nomura is finishing up her doctoral program this summer, and hopes to take her skills and optimism to an environmental NGO to continue working on environmental problems. The planet will certainly benefit from her expertise and experience – as her work on this project has already demonstrated, not even the sky is the limit to what she can achieve.

By Nancy Steinberg, posted June 18, 2024